Naming the Unnamed

A brief look at the role of African women in shaping contemporary African art

A cool evening breeze blows the smoke of a controlled fire in the backyard kitchen of a ten-person household. Heavy black pots of metal, forged by the able community blacksmith, are placed on top of the burning firewood to boil locally harvested rice. Heat fanned with hand fans by wrapper-covered, sweaty women, cleaning the sweat off their eyebrows with the loose ends of their wrappers. A common image painted of the pre-colonial African woman: caretaking, nurturing, and all that lies in between restrictive assigned roles characteristic of African societies suffering from the afterlife of patriarchal structures funneled into the continent via colonialism, structures upheld even after the deconstruction of colonialism. An image that erases the impact of women from endeavors women are not supposed to pioneer - one such being art.

A quick, brisk look through material on the formation of the contemporary African art movement leaves you wondering if it was all… men. The first International Congress of Black Writers and Artists was a spectacular event in black history, signifying a landmark event in black internationalism. However, there’s a staunch lack of women recorded as participants in or contributors to the event, so much so that the iconic photograph taken of all the delegates includes just one unnamed woman who has been speculated to be Marie-Rose Clara Perez, wife of Haitian activist and chair of the congress, Jean Price-Mars. This is despite contributions made by figures such as Christiane Yande Diop and Josephine Baker. The Ecole de Tunis movement in Algeria featured just one woman participant, Safia Farhat, who became the director of the Tunis Institute of Fine Arts in 1966. Minimal participation and exclusionary record-keeping have suppressed the impact of women during the early stages of the contemporary African art movement. Insidious as it is, it is of no surprise that the impact women artists, writers, and leaders had in molding the contemporary African movement and its theoretical predecessors is often overlooked or suppressed entirely. However, it is our duty as writers, artists, and academics to shed light on the brilliant artistry and creativity displayed by the women involved in this movement.

It is often thought that before colonialism, African women were involved in the creation of functional art, such as beautiful embroideries, pottery, baskets, braided hair patterns, and beaded garments, which have artistic merit. However, there is proof in certain parts of Africa that women created art for aesthetic and spiritual purposes. The Mende women of Sierra Leone were responsible for the creation of the ndoli jowei mask that served as an idealized symbol of female beauty and was used as the initiation mask for the Sande women’s initiation societies scattered across Western Africa. Women have always played a pivotal role in the societal makeup, despite its patriarchal nature, with art not being any different. This impact extends to the fight for independence across many African states.

Advocates for women’s rights during the independence boom and the eradication of apartheid were key to the inclusion of African women in art spaces. The Women’s Improvement Society of Nigeria's inaugural meeting on 1 August 1960 would lay the groundwork for feminist theoretical developments useful to the African continent. The July 1962 Conference of African Women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, where representatives from a dozen resistance organizations across fourteen African countries came together to discuss the end of colonialism, eradication of apartheid and segregation, and the need for inclusivity in African politics, was the foundation for the establishment of the Pan-African Women’s Organization and the declaration of 31 July as African Women’s day. The growth of women’s voices in political spaces would give a platform for women across the continent to gain access to education and pursue their goals and dreams.

During the immediate aftermath of the sweep of independence across the continent, nationalist values stapled in cultural reclamation and preservation emerged, with emphasis placed on art and writing. However, the women involved in shaping the art landscape across the continent today are largely forgotten. The students who created the famous Zaria Art Society in 1958 at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science, and Technology (now Ahmadu Bello University) were mentored by influential faculty member Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu, who served as a member of the university from 1955 to 1964. Josephine Ifueko Omigie became a member of the art society in 1959.

Algerian artist Baya, who was adopted by French painter Marguerite Caminat, is perhaps the most influential Northern African painter whose name has been forgotten over time. She first began painting in Caminat’s workshop. Impressed by her work, he sent some to Jean Peyrissac, who in turn showed them to Aime Maeght on his visit to Algeria. Maeght organized an exhibition of her work in 1947 at his gallery, introducing her to the keen attention of surrealists. Following the exhibition, she began work at the Madoura workshop in Vallauris, eventually meeting Pablo Picasso. Her style, categorized as naive, primitivist, art brut Arab mystery, gave her work a unique dreamlike quality that would go on to influence contemporary Arab paintings.

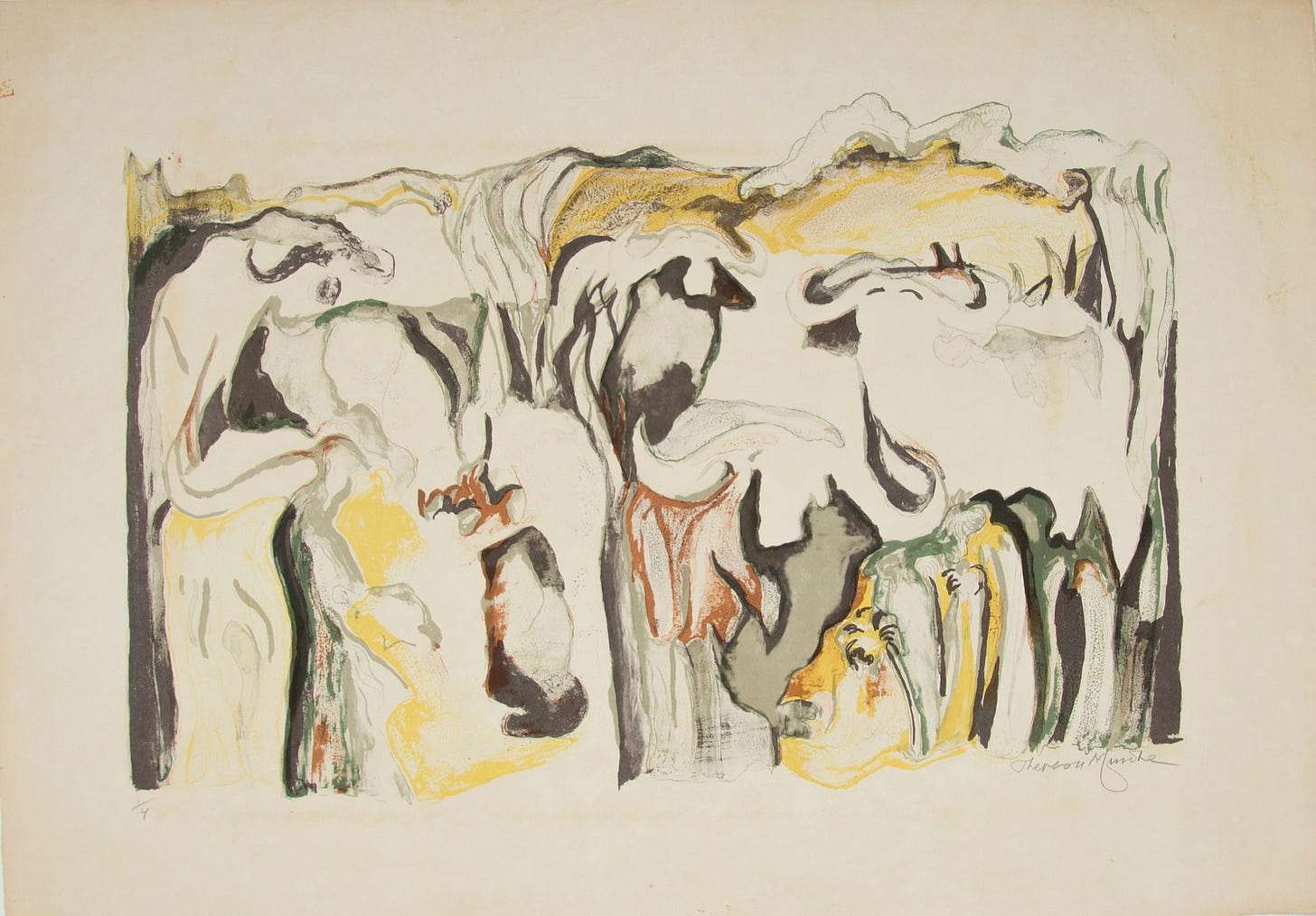

Ugandan-Kenyan visual artist Theresa Musoke, known for her rhythmic and expressionist style, had a similar impact on Eastern African artwork. Following formal training at the Makerere School of Fine Arts, she would go on to create Symbols of Birth and New Life, commissioned by the same school, win the Margaret Trowell Painting Prize, and exhibit Uganda Martyrs to Princess Margaret during her royal visit to Uganda in 1965.

These women, amongst many others not featured in this article, honed and showcased skills and techniques employed by contemporary African artists today in conjunction with their male counterparts. It is imperative that we shed light on these women and their impact as we push for a more inclusive art community.