Humanity through Time and Space

through the eyes of "Interstellar" and "The Metamorphosis of Birds"

I am currently in a transitional period. At the beginning of my Computer Engineering degree at Covenant University, I knew I would eventually face the reality of having to fill the hole left by my friends in four-year programs (CE is a five-year program) graduating before me. Four years and plenty of intriguing experiences later, I face the reality I once feared. Departure has always been a feature of my life, as with every human being throughout our species’ existence, but this phase of departure differs in emotional context from the others I’ve experienced. The difference is in the unavoidable feeling that you’re being left behind despite that not necessarily being the case. The fast-paced nature of the country I live in has undoubtedly contributed to the development of this feeling, but it’s a much deeper problem than that – the problem being the deep fear of abandonment that I faced but did not deal with after secondary school graduation. Leaving secondary school was heartbreaking, they were the people that I grew up with, but the friendships created, some carried over from secondary school, in university hold extreme importance to me.

In university, I’ve grown up. I think it’s disingenuous to suggest that I’ve fully discovered myself, I believe that’s a lifelong process, but I’ve found out more about my interests, my nature, and my behavior than I did during the six years of “growing up” I spent in secondary school. I acknowledge the banality of this experience, but a lot of this growth and self-discovery is why the connections I have with the friends I’ve made in university are much more profound than some of the others. They accepted the Tolu that I didn’t know existed and loved me despite the flaws that I have, most of which I was painfully oblivious to. Of course, I accepted them for who they were, and with the epiphanies of the complexities of human relationships each of us experienced, the love developed over time and became much more than just loving because. My friends became a part of me. So, this sudden chasm placed between our physical interactions has created that gaping hole I referred to earlier.

I use Twitter a lot (calling it “X” is an insult to me) and recently tweeted about the deep loneliness and disconnection I’ve felt in the past few weeks. It made me think about my favorite thing about Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar. Brand, Romilly, and Cooper were faced with the challenge of picking the next planet to visit after the failure of their first expedition, and the death of Doyle. They had to take many things into consideration; the fuel cost, the time cost, and the probability of habitability of each planet left, but Cooper added that there was one more intangible factor to consider, Brand’s love for Doctor Edmund, an explorer whose planet was one of the choices presented alongside Doctor Mann’s planet. What struck me most was that Doctor Brand was willing to abandon the “logical” choice to select Doctor Mann’s planet for a slight chance to be reunited with the person she loved the most.

“Maybe it means something more, something we can’t yet understand. Maybe it’s some evidence, some artifact of a higher dimension we just can’t perceive. I’m drawn across the universe to someone I haven’t seen in a decade, who I know is probably dead. Love is the one thing we’re capable of perceiving that transcends the dimensions of time and space.”

Interstellar beyond the grandeur of space exploration and attempting to save humanity from extinction, is a film about deep love. The love between a father, Cooper, and daughter, Murphy, was so powerful that it created structures beyond the scale of our current understanding to provide answers to humanity’s problems that they could only access through the memories ingrained within their psyche. Cooper throughout the runtime of the film (honestly, the three hours feel like thirty minutes every time) realized that the driving force of the universe created by Christopher Nolan was not gravity or time, it was love. It was through love that he overcame all the obstacles presented to him and found a way back to his kids, albeit one.

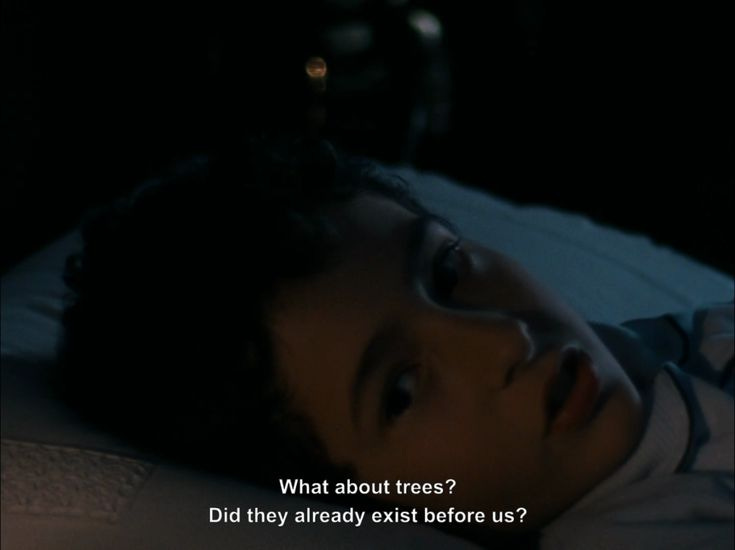

This movie emphasized the true power of this mixture of completely polarizing emotions and its accessibility even in separation through time and death. A theme so present, so beautiful, so endearing in Catarina Vasconcelos’ A Metamorfose dos Passaros (or The Metamorphosis of Birds). There are many things I can say about the technicalities of this movie and the brilliant choice to shoot in a 4:3 ratio as opposed to a wide ratio, but nothing is as meaningful in this current moment as the story.

The movie begins with Beatriz and Henrique, two Portuguese nationals separated by Henrique’s long periods at sea as a naval officer, sending letters to each other with updates about their lives, their growing children, and the love they share. This is beside the point and something I’ll probably deal with in another write-up, but I want to experience such deep yearning that daily life becomes almost impossible to bear. Anyway, in the film, Beatriz and Henrique narrate their letters to each other, each one filled with more yearning and love than the last.

“On the line that separates the sea and sky, all our loved ones live,” Henrique writes, talking about the collective thoughts amongst crew members on board his ship. They looked at the vast amount of ocean in front of them, land eluding, and could only find comfort in the beauty of the horizon that contained all their memories and experiences.

These letters last decades, and their children grow older and wiser. Jacinto, the eldest son, rejects his father’s life’s work of colonial efforts in Africa and even gets married. But the letters suddenly stop. Beatriz dies.

“We observed life as if it were in a frame and outside of it everything kept moving on,” Jacinto narrates as he reflects on his mother and the life of simple pleasures she lived. He saw her as a tree, whose branches allowed her five children to swing, but Jacinto saw himself as a bird and his mother as the tree he would make his nest on as he changed throughout his lifetime. The tree is no more, and a deep sadness comes upon him that he finds hard to shake off even as he grows older and more aware of his surroundings.

“He thought of all the mothers that had died and realized that what he felt was unoriginal, it was even quite banal, but he had it in mind that his mother was the only one who had been a tree.”

A few years later, he has a daughter with his wife, and the joy he thought he could no longer feel races through his bones like electricity through wires. That joy is cut short by another tragedy, his wife and daughter’s mother dies fifteen years after her childbirth. He and his daughter are left to face the brutal reality of living without mothers.

“Mothers were the only gods who had non-believers on earth,” Catarina says as she reflects on the short time she had to spend with her mother and narrates the dream she had of their reunion another fifteen years later.

Catarina and Jacinto, Henrique in real life, reflect on the grief that came with the death of their mothers. They talk about going to heaven, the place where uncertainty resides, and reaching the summit of the tallest mountain to look down at the earth’s magnificence hoping to see the faces of their mothers reflected at them. Ultimately, they go out to sea with the memories of their treasured ones etched on their skins, never to leave.

On reflection, both films offer similar perspectives of love; one told through time and space in grandeur, the other told in simplicity. Love is a power that transcends any barrier placed in front of it, because of this I do not have to fear the uncertainty I'm currently faced with, or the gaping hole being left behind by those going a little bit ahead of me. Instead, I can make calls from deep within my heart and know that people are out there, close, or far, to hear and answer those calls.